Innovation in Tropical Forest Conservation: Q&A with Dr. Mark Mulligan

Swamp forest in Western Colombia. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler.

Mark Mulligan makes maps for the masses. In his work on tropical forests, Mulligan uses GIS, modeling, remote sensing, and lab experiments to turn research into datasets and policy support systems, which are available online for use in development, decision-making, and education.

“The democratization of data and movement of very technical scientific data from the realm of experts to much broader use in society” is the biggest development in conservation over the last decade, Mulligan told mongabay.com.

Now that the “democratization of data” has become more mainstream, Mulligan has focused on developing policy support systems which, instead of static maps, provide “a web-based spatial analysis environment that integrates massive global datasets and analytical tools” for decision-making.

“Since 2006, we have been bringing together global spatial datasets around environmental issues and making them more accessible and useful to all in order to highlight tropical forest conservation issues and also build capacity to use these data for conservation purposes…Though in many cases the data is available elsewhere, it was only really available to remote sensing experts and by making it visual in Google Earth and downloadable in clean and easy to use GIS formats, we made it accessible to all,” Mulligan told mongabay.com, adding, “Maps are very powerful tools for understanding, communicating and managing the environment.”

Dr. Mark Mulligan is a reader in Geography at King’s College London and is on the Council of the Royal Geographical Society. He is also senior fellow of the UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre currently leading research projects on benefit sharing mechanisms for water in the Andes, desertification in Southern Europe and North Africa, and the hydrological ecosystem services of Madagascar’s forests.

AN INTERVIEW WITH DR. MARK MULLIGAN

Mongabay: What is your background? How long have you worked in tropical forest conservation and in what geographies? What is your area of focus?

Mark Mulligan: I am a Geographer who works on the disciplinary boundary of Geography and Ecology. Before doing a BSc in Physical Geography at Bristol University, I took courses in Geography, Biology and Computer Science. Upon completion of my BSc in 1991, I got involved in the Brunei Rainforest Project, a joint project between the University of Brunei Darussalam (UBD) and the Royal Geographical Society (RGS) to establish a permanent field studies center for rainforest research just inside the border of the 48,000 hectare Batu Apoi Forest Reserve of Temburong District. That fuelled my already strong interest in tropical forests.

I then completed my PhD on monitoring and modeling the impact of hydro-climatic variability on Mediterranean shrub-lands, taking some time out to join the RGS Nepal Middle Hills Project. During this time I was fortunate to meet and see presentations from a number of British ecologists who were working in Colombia, including Paul Salaman. Having already decided that I would pursue a life in better understanding tropical forests, I then decided to start that work in Colombia. I began in 1994 when I took up a lectureship at King’s College London and started working in cloud forests—rather special forests occurring in the cloud belts of tropical mountains meaning that they are frequently and persistently immersed in clouds. These isolated forests are highly diverse with high levels of endemism and are hydrologically unique compared with all other forests, since they have the potential to increase water flows compared with agricultural land because they ‘harvest’ much of this passing fog, which otherwise would pass by.

I have always worked with overseas PhD students and have first supervised some twenty-eight to successful completion of their PhD since 2000 and have another four in progress. These students are the real enablers of much of our tropical forests related activity and many are now in post in tropical research institutes around the world.

We worked intensively over many years at sites in southern Colombia setting up some of the first heavily instrumented cloud forests at a time when Colombia was a little more difficult to work in than it is now and when the technology for instrumenting remote environments that have no electricity and little sunlight was much more challenging than today. We became experts in dealing with cranky electronics as well as in ecology and hydrology. By collecting extensive data when we were in the field and continuous electronic monitoring when we were not, we understood more of the role of these forests in supporting downstream flows of water—what we now call their ecosystem service value. When we were not in the field we built a laboratory ‘cloud chamber’ in a basement of King’s College London in central London to understand the detail of how these low-level clouds (fogs) interact with tree structures affecting their hydrology and productivity.

During this period we also worked in the Philippines with ESSC, in Thailand and in other parts of Central and South America, always combining an interest in technology with an interest in biophysical processes to find ways that the former could help better understand the latter. This extended to the forerunner of today’s conservation drones, though when we crashed our remote control helicopter (fortunately without the cameras onboard) we moved to deploying the cameras on helium filled balloons for our work mapping tree species richness along tributaries of the Amazon.

Using helium filled balloons for low altitude aerial photography of tree diversity in the Ecuadorian Amazon. Photo courtesy of Mark Mulligan. |

My area of focus has morphed over the years. Initially we worked intensively in the field to better understand the physical processes operating in tropical forests, with particular emphasis on the impacts of land use change whereas now we combine fieldwork with larger scale, more policy relevant, Geographical Information Systems (GIS) and spatial modeling work to develop and deploy Policy Support Systems (PSS). These ‘big-data’ computational systems integrate the knowledge that we have been making it more accessible and more useful to all. So, nowadays, when we are not in a hot humid tropical forest surrounded by trees we are in a hot dry server rooms, surrounded by computers.

Mongabay: Are you personally involved in any projects or research that represent emerging innovation in tropical forest conservation?

Mark Mulligan: Since 2006 we have been bringing together global spatial datasets around environmental issues and making them more accessible and useful to all in order to highlight tropical forest conservation issues and also build capacity to use these data for conservation purposes. In 2006, we were the first to produce Google Earth and Google maps visualizations of WDPA protected areas and global forest loss using an earlier of Matt Hansen’s datasets (VCF), just as World Resource Institute does now Global Forest Watch with Hansen’s latest product GFC. We improved, and made a number of datasets available for easy visualization and download at geodata.policysupport.org,

a free conservation data portal, including data for land use change, rainfall, water bodies, sea level rise, cloudforests, clouds, and places. These brought easy-to-use visualizations and usable data to those working on conservation throughout the world. Though in many cases the data is available elsewhere, it was only really available to remote sensing experts and by making it visual in Google Earth and downloadable in clean and easy to use GIS formats, we made it accessible to all. Maps are very powerful tools for understanding, communicating and managing the environment. Many of these datasets were commentable using a Geowiki, where users could add new sites to the cloud forest map or comment on the deforestation map based on their own experience. The Geowiki was also used in a number of crowdsourcing projects, including one to map the world’s dams, more than 36,000 of which have now been mapped and which tell us which forests are providing services to downstream dams.

This democratization of data was innovative at the time but is becoming mainstream now. Through the hard work of those at NASA, ESA, JAXA and elsewhere who collect earth observation data, those like Matt Hansen and others who create valuable products from the raw data, and those like us who then invest the time to make those products accessible to the non-expert, together we are making human impacts on the environment more transparent and that has to be a good thing.

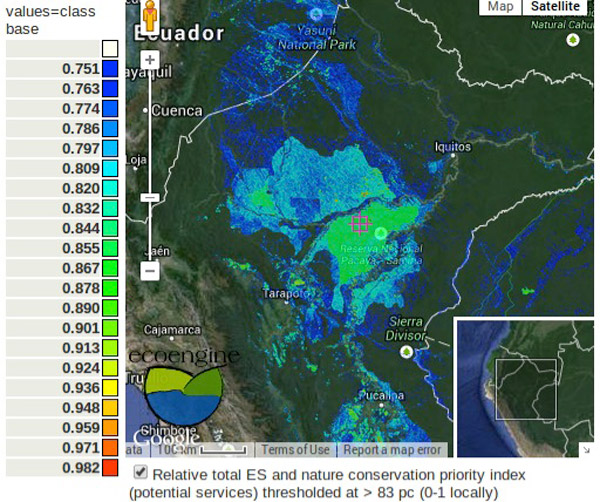

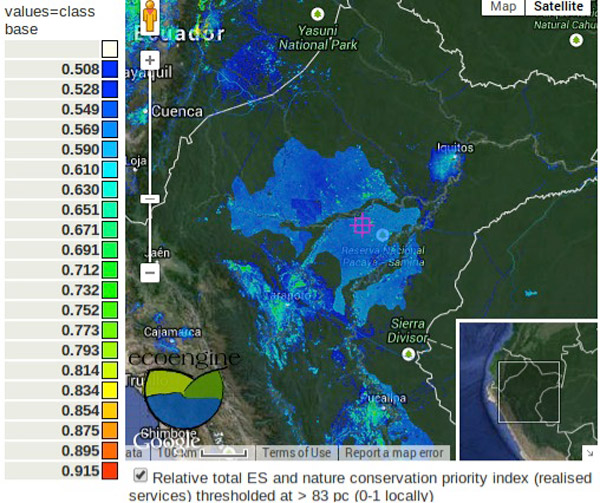

Over the last few years we have worked less on the provision of data visualizations and downloads (though many still use the products that we maintain at geodata.policysupport.org). Now, we develop and deploy policy support systems (PSS). These innovate because instead of providing static data or visualizations of mapped data, they provide a web-based spatial analysis environment that integrates massive global datasets and analytical tools for generating knowledge and answers to conservation questions. These PSS are made freely available at www.policysupport.org and are locally relevant but applicable anywhere globally with datasets that we provide. For example within 10 minutes of work the Co$ting Nature PSS

can be used by anyone to develop a spatial conservation prioritization like the one below, for anywhere in the world, based on mapped distributions of biodiversity, ecosystem services, current development pressure, future development threat:

Top 17 percent of aggregate conservation priority (incl. potential ecosystem services). Image courtesy of Mark Mulligan.

Top 17 percent of aggregate conservation priority (incl. realized ecosystem services). Image courtesy of Mark Mulligan.

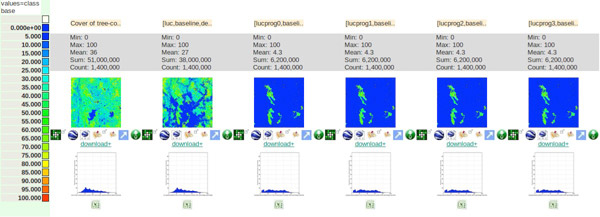

…and the user’s own valuation of which of these are important where. The WaterWorld PSS can be used to examine the role of current land use in the provision of water quality and quantity to people locally and downstream and, through its connection with a range of deforestation monitoring systems including Terra-i and GFC, can be used to examine the impacts of recent and projected future land use change on water, such as the example for Medellin given below.

200-year deforestation scenario for the area around Medellin, Colombia based on recent rates and 70% effectiveness of protected areas. Scale represents percent of forest cover from current (left) to +200 years right in steps of 20, 65, 110,155 and 200 years. Image courtesy of Mark Mulligan. Click to enlarge.

Unlike the complex scientific software that went before, these systems can be used on the simplest of computers by anyone who is familiar with other web-tools like gmail, twitter, ebay or amazon. They are used to support conservation decision making in remote environments where local datasets may be lacking and GIS capacity less developed. The tools thus bring conservation-, hydro- and eco-literacy to all, creating a level playing field where all stakeholders in a decision have access to the most detailed spatial scientific data and tools to build scenarios and understand impacts. They are starting to be used in ecosystem services assessment, conservation planning and negotiation.

Mongabay: What do you see as the biggest development or developments over the past decade in tropical forest conservation?

Mark Mulligan: The democratization of data and movement of very technical scientific data from the realm of experts to much broader use in society. This has been driven largely by technological developments but also by increasing demand from society for achieving policy-relevance in academic and scientific research. It is still less than 10 years since Google Earth came into existence in its current form and Google Earth is surely a notable example of that trend and an important conservation tool. A number of other organizations have also worked tirelessly to bring scientific datasets or tools into policy and practical use, notable examples with tropical forest relevance being GBIF, Terra-i, CSI, RAINFOR, and InVEST, though there are many others.

Mongabay: What’s the next big thing in forest conservation? What approaches or ideas are emerging or have recently emerged? What will be the catalyst for the next big breakthrough?

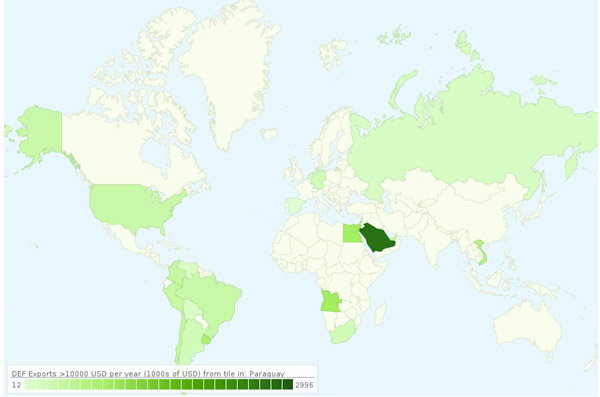

Mark Mulligan: Who knows? The big thing isn’t always the thing that has greatest success in actual conservation outcomes. I am sure we can all think of examples of big tropical forest things that went nowhere. Increasingly transparent and policy-relevant data and research will continue to be key. We now know where the tropics is deforesting… but so what? What does it mean and what can we do? I think that connecting deforestation with its direct positive impacts (jobs, food) and negative impacts (climate, water, biodiversity) is going to be important in ensuring net benefit for all from land use change that occurs. We are certainly working to improve our tools ability to examine the positive and negative impacts of recent and projected forest loss so that we can get closer in transparency not just to where forests are being lost but also what the actual costs and benefits are to local and global stakeholders. Moreover connecting deforestation datasets to commodity flow datasets as we have started with WaterWorld and Co$ting Nature (see below) is needed to help us understand whose consumption is driving tropical deforestation and to better connect consumers with the outcomes of their choices.

5Paraguay.jpg:

Source of export earnings for products grown in areas of Paraguay in which deforestation is occurring, from www.policysupport.org/costingnature.

The increasing attention on climate change will – no doubt – continue to be a catalyst for tropical forest conservation given the role of tropical forests in the global carbon balance but I hope that IPCC’s cousin IPBES—the platform for biodiversity and ecosystem services takes a major role in making the excellent, policy-relevant tropical forest science being done around the world more accessible to the political, commercial and consumer audiences in whose hands our remaining tropical forests are. Tropical forests and the myriad species occupying them are—after all—being lost faster and more irreversibly than our climate is changing and with projected impacts on us that we are equally unsure about. We need the same level of collaboration and innovation in ecosystem service modeling as we had in General Circulation Models (GCMs) so that we can get a handle on how to manage our remaining forests sustainably and understand the impacts of not doing so.

Mongabay: What isn’t working in conservation but is still receiving unwarranted levels of support?

Mark Mulligan: I am worried about protected areas. I see the map of the global protected areas network at www.protectedplanet.net as a rather dangerous map – it rather gives the impression that the areas in blue actually are protected and the conservation task is done. I have worked in enough tropical forest protected areas to know that many are not effectively protected. In fact most of the sites I have ever worked in have seen significant development a few years after we got there. Once a site becomes accessible enough for international scientists to visit, it is not long before the roads, oil and mining arrives. Protected areas clearly are successful but we have to be realistic about to what extent they really are protected, hence the importance of making more transparent where deforestation is taking place inside protected area boundaries as we did in RALUCIAPA, as Terra-i does, and as Global Forest Watch now does.

I am also worried about the ecosystem services ‘bandwagon’. I know that many conservation organizations have taken it up rapidly, but for me as someone who maps ecosystem services and then models the impacts of land use change upon them I see the concept having some pretty serious flaws for some conservation purposes. By definition an ecosystem service is not a service until someone is around to use it either directly as a person or through agriculture, infrastructure or some other dependency. This means that (often small, highly threatened) protected areas close to and upstream of large urban centers and populated areas (such as many of the Andean cloud forests) are a high priority from an ecosystem services point of view, providing water, hazard mitigation and nature-based tourism services to large nearby populations. But for more remote sites and the great wilderness areas, there are often few people around or close enough downstream to realize the potential services provided. Except for their role in atmospheric services like carbon sequestration and storage, the great wilderness areas, including many tropical lowland forests do not figure highly in ecosystem services metrics so we have to be careful in using those metrics as an argument for conservation in such areas. In fact the only way to increase the ecosystem services that those areas provide is to deforest, move people, infrastructure and agriculture in to create the necessary dependencies.

Related articles

Malaysia imperils forest reserves and sea turtle nesting ground for industrial site (photos)

(04/15/2014) Plans for an industrial site threaten one of Malaysia’s only marine turtle nesting beaches and a forest home to rare trees and mammals, according to local activists. Recently, the state government of Perak approved two industrial project inside Tanjung Hantu Permanent Forest Reserve. But activists say these will not only cut into the reserve, but also scare away nesting turtles from Pasir Panjang.

Next big idea in forest conservation? Empowering everyone to watch over forests

(04/10/2014) Nigel Sizer has worked on the forefront of global forest issues for decades. Currently, he is the Global Director of the World Resource Institute’s (WRI) Forests Program, whose projects include the Global Forest Watch, the Forest Legality Alliance, and the Global Restoration Initiative. These programs work with governments, businesses, and civil society with the aim of sustaining forests for generations to come.

Nearly 90 percent of logging in the DRC is illegal

(04/08/2014) The forestry sector in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is completely out of control, according to a new eye-opening report. Put together by the Chatham House, the report estimates that at least 87 percent of logging in the DRC was illegal in 2011, making the DRC possibly the most high-risk country in the world for purchasing legal wood products.

Next big idea in forest conservation? Connecting deforestation to disease

(04/03/2014) Thomas Gillespie is concerned with the connections between conservation and disease, with a particular emphasis on primates. Much of his research examines the places where humans and animals are at a high risk of exchanging pathogens, and how human-caused disturbances, such as deforestation, can change disease dynamics and impacts.

Next big idea in forest conservation? Quantifying the cost of forest degradation

(03/27/2014) How much is a forest really worth? And what is the cost of forest degradation? These values are difficult to estimate, but according to Dr. Phillip Fearnside, we need to do a better job. For nearly forty years, Fearnside has lived in Amazonia doing ecological research, looking at the value of forests in terms of environmental or ecosystem services such as carbon storage, water cycling, and biodiversity preservation. Fearnside then works to convert these services into a basis for sustainable development for rural populations.

Just how bad is the logging crisis in Myanmar? 72 percent of exports illegal

(03/26/2014) Just days before Myanmar, also known as Burma, implements a ban on exporting raw logs, the Environmental Investigative Agency (EIA) has released a new report that captures the sheer scale of the country’s illegal logging crisis. According to the EIA, new data shows that 72 percent of logs exported from Myanmar between 2000-2013 were illegally harvested.