Koh and Wich testing their drone in Switzerland. The conservation drone has been equipped with various cameras including the GoPro HD Hero video camera, the Canon IXUS 220 HS, and the Pentax Optio WG-1 GPS. Image courtesy of Lian Pin Koh.

Inexpensive aerial drones can help conservationists map forests, monitor land use change like deforestation, and track wildlife in remote and inaccessible areas, reports a new study published in the journal Tropical Conservation Science.

Lian Pin Koh, an ecologist at the ETH Zürich, and Serge Wich, a biologist at the University of Zürich and PanEco, built the “conservation drone” by outfitting a model airplane with a camera, sensors and a GPS unit. The flight path of the unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) was programmed by clicking on waypoints in a Google Earth map interface, enabling the researchers to target specific forest areas for surveying and mapping.

“The idea for developing this low-cost drone came to me during one of my field trips to Borneo in 2004,” Koh told mongabay.com during a February 2012 interview. “A very exhausting day of fieldwork made me wish for a remote control aircraft that I could send into the forest to do the work for me so that I could take a break the next day.” |

Koh and Wich tested the drone above rainforests on the Indonesian island of Sumatra. After several 25-minute flights, they were able to stitch together aerial photographs to produce land use and land cover maps, document a wild orangutan atop a tree and a Sumatran elephant in a clearing, and detect agricultural conversion, demonstrating the useful conservation and environmental applications of the drone.

The findings are significant because conservation surveying and monitoring can be a costly endeavor. The researchers cite orangutan population surveys as an example.

“Ground surveys of orangutan populations (Pongo spp.) in Sumatra, Indonesia can cost up to ~$250,000 for a two-year survey cycle,” they write. “Due to this high cost, surveys are not conducted at the frequency required for proper analysis and monitoring of population trends. Furthermore, some remote tropical forests have never been surveyed for biodiversity due to difficult and inaccessible terrain.”

Orangutan (top) and elephant (bottom) as photographed by the conservation drone. Courtesy of Lian Pin Koh.

“The use of Conservation Drones could lead to significant savings in terms of time, manpower and financial resources for local conservation workers and researchers, which would increase the efficiency of monitoring and surveying forests and wildlife in the developing tropics. We believe that Conservation Drones could be a game-changer and might soon become a standard technique in conservation efforts and research in the tropics and elsewhere.”

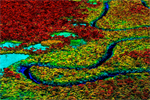

Koh and Wich are now developing a more advanced version of their drone, including one outfitted with near infra-red, infra-red and ultra-violet cameras. The researchers recently tested new designs above rhino and tiger habitat in Nepal.

CITATION: Koh, L. P. And Wich, S. A. 2012. Dawn of drone ecology: low-cost autonomous aerial vehicles for conservation. Tropical Conservation Science Vol. 5(2):121-132.

Related articles

Model airplane used to monitor rainforests – conservation drones take flight

(02/23/2012) Conservationists have converted a remote-controlled plane into a potent tool for conservation. Using seed funding from the National Geographic Society, The Orangutan Conservancy, and the Denver Zoo, Lian Pin Koh, an ecologist at the ETH Zürich, and Serge Wich, a biologist at the University of Zürich and PanEco, have developed a conservation drone equipped with cameras, sensors and GPS. So far they have used the remote-controlled aircraft to map deforestation, count orangutans and other endangered species, and get a bird’s eye view of hard-to-access forest areas in North Sumatra, Indonesia.

Breakthrough technology enables 3D mapping of rainforests, tree by tree

(10/24/2011) High above the Amazon rainforest in Peru, a team of scientists and technicians is conducting an ambitious experiment: a biological survey of a never-before-explored tract of remote and inaccessible cloud forest. They are doing so using an advanced system that enables them to map the three-dimensional physical structure of the forest as well as its chemical and optical properties. The scientists hope to determine not only what species may lie below but also how the ecosystem is responding to last year’s drought—the worst ever recorded in the Amazon—as well as help Peru develop a better mechanism for monitoring deforestation and degradation.