Remote-controlled plane offers bird’s-eye approach to conservation.

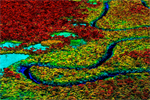

Aerial photograph from the drone showing forest clearing. Courtesy of Lian Pin Koh.

Conservationists have converted a remote-controlled plane into a potent tool for conservation.

Using seed funding from the National Geographic Society, The Orangutan Conservancy, and the Denver Zoo, Lian Pin Koh, an ecologist at the ETH Zürich, and Serge Wich, a biologist at the University of Zürich and PanEco, have developed a conservation drone equipped with cameras, sensors and GPS. So far they have used the remote-controlled aircraft to map deforestation, count orangutans and other endangered species, and get a bird’s eye view of hard-to-access forest areas in North Sumatra, Indonesia.

“The main goal of this project is to develop low-cost Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) that every conservation biologist in the tropics can use for surveying forests and biodiversity,” said Koh via email. “Drones are already being used for many purposes including the military, agriculture, and even in Hollywood for filming. But they are still not commonly used for conservation purposes.”

The reason, says Koh, is the high cost of commercial systems, which can run $10,000-50,000. Koh’s first drone cost less than $2,000 and can be carried in a backpack.

“The idea for developing this low-cost drone came to me during one of my field trips to Borneo in 2004,” Koh told mongabay.com. “A very exhausting day of fieldwork made me wish for a remote control aircraft that I could send into the forest to do the work for me so that I could take a break the next day.” |

“The drone is almost fully autonomous, which means it can take-off and fly on autopilot,” Koh explained. “The user pre-programs each mission on a laptop computer by clicking waypoints along a planned flight path on a Google Map. Based on this flight path and the onboard sensors (GPS, altitude sensor, airspeed sensor, etc), the drone will take off automatically, fly to every waypoint, and then return to the user. During the mission, the drone can take photographs or videos depending on the camera system installed.”

For anyone who has spent hours tracking over rough terrain in the tropical rainforest, the appeal of a conservation drone is immediately obvious.

“This may offer a cost-effective way of counting wildlife over difficult terrain,” Stuart Pimm, an ecologist at Duke University who runs the conservation non-profit Saving Species, told mongabay.com. “Having imagery of far higher resolution than from satellites is essential for such work and it offers a viable alternative in places where helicopter or plane costs are too high.”

There are also scenarios where a drones can be an alternative to satellite imagery.

“Low-cost drones can be an effective alternative to satellite images for mapping the landscape,” Koh told mongabay.com. “In fact, drones can perform better than satellite data in cases where an area needs to be mapped in real-time and repeatedly.”

To date, Koh and Wich have used the drone in Aras Napal, close to the Gunung Leuser Conservation Area in Sumatra. During their four days of testing, the drone flew 30 missions — collecting hundreds of photos and hours of video — without a single crash. A mission, which typically lasts about 25 minutes, can cover 50 hectares.

“The drone took pictures of areas where logging occurred, and areas where oil palm are planted right next to a river, which is very damaging to the river ecosystem,” Koh said. “It also took pictures of an orangutan who was feeding on top of a palm tree, as well as elephants on the ground. During one mission, the drone also recorded a video showing smoke rising from a forest area. These test missions demonstrate that the drone can indeed be used for the purposes it has been developed for.”

Orangutan (top) and elephant (bottom) as photographed by the conservation drone. Courtesy of Lian Pin Koh.

Koh envisions using the drone to monitor forests, detect fires, and map land use in real-time. He believes the low cost will open up the drone to a wide range of other applications.

“My dream is that in the future, every field ecologist will have a drone as part of their toolkit, since it doesn’t cost more than a good pair of binoculars!”

Koh says the response to the drone so far has been overwhelmingly positive from conservationists.

“We have already attracted the attention of field researchers around the world, who are asking us to go to their study locations for further test flights. These locations include Borneo, Africa and even Antarctica to film penguins!”

Related articles

Scientists create high resolution, 3D maps of forests in Madagascar

(02/15/2012) A team of scientists has created the first high resolution maps of remote forests in Madagascar. The effort, which is written up in the journal Carbon Balance and Management, will help more accurately register the amount of carbon stored in Madagascar’s forests, potentially giving the impoverished country access to carbon-based finance under the proposed REDD (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and forest Degradation) program.

Laser-based forest mapping as accurate for carbon as on-the-ground plot sampling

(11/02/2011) Two new research papers show that an advanced laser-based system for forest monitoring is at least as accurate as traditional plot-based assessments when it comes to measuring carbon in tropical forests.

Breakthrough technology enables 3D mapping of rainforests, tree by tree

(10/24/2011) High above the Amazon rainforest in Peru, a team of scientists and technicians is conducting an ambitious experiment: a biological survey of a never-before-explored tract of remote and inaccessible cloud forest. They are doing so using an advanced system that enables them to map the three-dimensional physical structure of the forest as well as its chemical and optical properties. The scientists hope to determine not only what species may lie below but also how the ecosystem is responding to last year’s drought—the worst ever recorded in the Amazon—as well as help Peru develop a better mechanism for monitoring deforestation and degradation.

(05/14/2011) A new animation created using Google Earth offers a tour of an area of forest slated for destruction by logging companies. The animation, created by WWF-Indonesia and David Tryse, with technical assistance from Google Earth Outreach, highlights the rainforest of the Bukit Tigapuluh landscape in Sumatra, the only island in the world that is home to Sumatran tigers, elephants, rhinos, and orangutans. All of these species are considered endangered or critically endangered due to habitat destruction or poaching.

Google Earth now features 3-D trees

(11/29/2010) With world leaders meeting at climate talks in Cancun to discuss the future of forests, Google has added 3D trees to the latest version of Google Earth. Google has populated several major cities with more than 80 million virtual trees based on an automated process that identifies trees in satellite images. The realistic 3D representations are based on actual tree species found in urban areas. But Google has also extended realistic tree coverage to sites in some of the world’s most biologically diverse forests.

How satellites are used in conservation

(04/13/2009) In October 2008 scientists with the Royal Botanical Garden at Kew discovered a host of previously unknown species in a remote highland forest in Mozambique. The find was no accident: three years earlier, conservationist Julian Bayliss identified the site—Mount Mabu—using Google Earth, a tool that’s rapidly becoming a critical part of conservation efforts around the world. As the discovery in Mozambique suggests, remote sensing is being used for a bewildering array of applications, from monitoring sea ice to detecting deforestation to tracking wildlife. The number of uses grows as the technology matures and becomes more widely available. Google Earth may represent a critical point, bringing the power of remote sensing to the masses and allowing anyone with an Internet connection to attach data to a geographic representation of Earth.

Development of Google Earth a watershed moment for the environment

(03/31/2009) Satellites have long been used to detect and monitor environmental change, but capabilities have vastly improved since the early 1970s when Landsat images were first revealed to the public. Today Google Earth has democratized the availability of satellite imagery, putting high resolution images of the planet within reach of anyone with access to the Internet. In the process, Google Earth has emerged as potent tool for conservation, allowing scientists, activists, and even the general public to create compelling presentations that reach and engage the masses. One of the more prolific developers of Google Earth conservation applications is David Tryse. Neither a scientist nor a formal conservationist, Tryse’s concern for the welfare of the planet led him develop a KML for the Zoological Society of London’s EDGE of Existence program, an initiative to promote awareness of and generating conservation funding for 100 of the world’s rarest species. The KML allows people to surf the planet to see photos of endangered species, information about their habitat, and the threats they face. Tryse has since developed a deforestation tracking application, a KML that highlights hydroelectric threats to Borneo’s rivers, and oil spills and is working on a new tool that will make it even easier for people to create visualizations on Google Earth. Tryse believes the development of Google Earth is a watershed moment for conservation and the environmental movement.

Photos: Google Earth used to find new species

(12/22/2008) Scientists have used Google Earth to find a previously unknown trove of biological diversity in Mozambique, reports the Royal Botanic Gardens in Kew. Scouring satellite images via Google Earth for potential conservation sites at elevations of 1600 meters or more, Julian Bayliss a locally-based conservationist, in 2005 spotted a 7,000-hectare tract of forest on Mount Mabu. The scientifically unexplored forest had previously only been known to villagers. Subsequent expeditions in October and November this year turned up hundreds of species of plants and animals, including some that are new to science.